By Morgan Polikoff & David M. Houston

The headlines on the effects of COVID on kids could hardly be gloomier. Students are “far, far behind,” argued Harvard professor Tom Kane in The Atlantic. The New York Times described how kids will need “at least three years” to catch up to where they should be. The warnings are dire on nonacademic outcomes, too — the surgeon general issued an advisory late last year on the “mental health crisis” affecting America’s youth.

Yet, parents don’t seem worried about any of this. And that upbeat outlook is making it nearly impossible for education leaders to address the very real negative effects of COVID on students.

Indeed, there are serious concerns about kids’ academic and emotional well-being. Students are far behind where they would have been if not for COVID, especially in mathematics. The effects are larger for those who were already further behind, and for kids in “high-poverty schools that stayed remote.” Mental health issues among children were already pervasive before COVID and seem to have been made worse by prolonged shutdowns. In response to these problems, the federal government has poured billions into schools to support interventions like tutoring, summer programs and new air filtration systems.

This certainly sounds like a crisis — but that’s not how parents are reacting. While many did express concern early on in the pandemic, recent surveys — including ones we have directed — find parents aren’t so concerned anymore. They aren’t worried about academics, and they aren’t worried about mental health. And as a result, they aren’t especially interested in the COVID recovery interventions schools are offering.

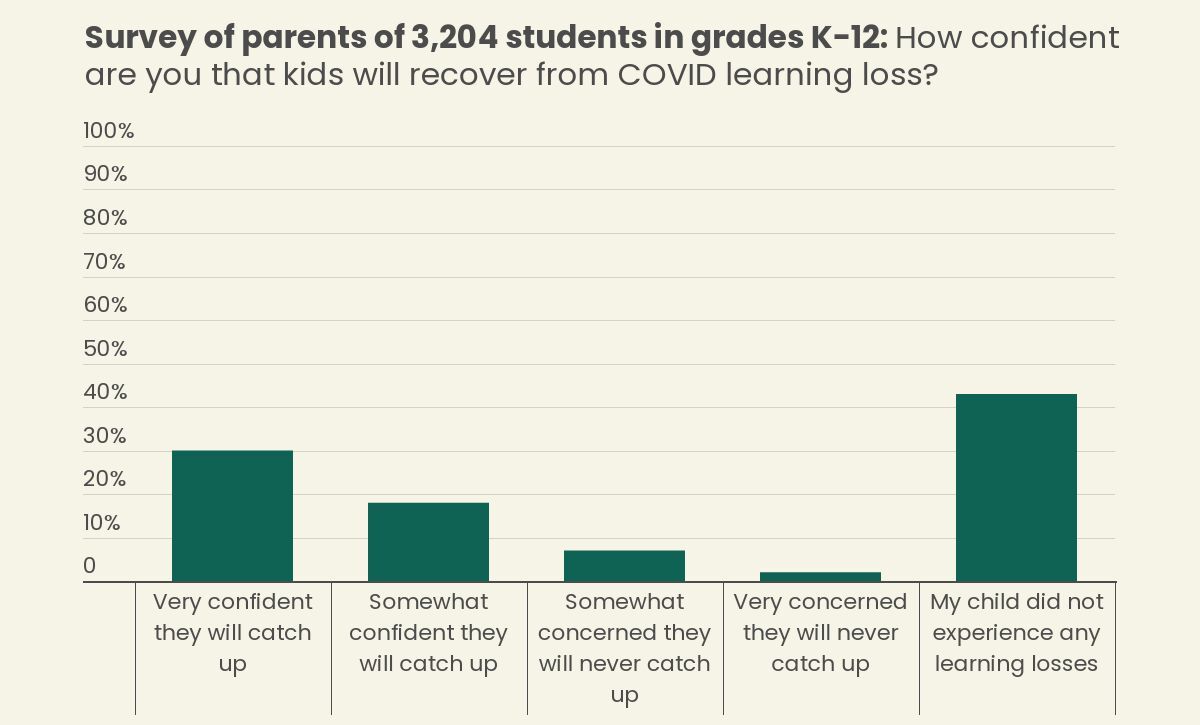

The Education Next national survey found that parents of only 9% of K-12 students

were very or somewhat concerned their child would ever catch up to where they should be. In fact, parents of 43% said their kids experienced no learning losses at all! The Understanding America Study found only about 15% of parents were concerned or very concerned about the amount their child was learning or their psychological well-being. And the PACE/USC Rossier poll of California voters found that 54% of parents think their kids’ academic performance is better than before COVID, versus just 23% who think it’s worse.

Why the huge disconnect? We have a few theories, but we don’t have the hard data needed to answer this question. Certainly one reason could be that parents aren’t getting the kinds of information they would normally get about their kids’ performance. Grade inflation has accelerated during the pandemic, while at the same time many have questioned the quality and utility of state tests administered during COVID. And parents may have more relative than absolute ways of thinking about their kids’ performance — if everyone is struggling, maybe my child is still above average.

But beyond this explanation, it’s hard for parents to imagine where their child would be academically and emotionally if, in some alternate universe, the pandemic had never happened — what experts call the counterfactual. How do parents know how much their child is supposed to grow from year to year in math achievement when, at best, their sources of information include grades and standardized test results that come infrequently and are often hard to understand?

Of course, another explanation could be that parents are right and the experts are wrong. Maybe the kids actually are okay. But this is more plausible with regard to more difficult-to-measure things like emotional well-being than it is with regard to math achievement, where the evidence of losses seems quite overwhelming.

Regardless of the reason, this disconnect has huge implications for solving problems caused by the pandemic. For starters, parents who aren’t concerned aren’t likely to enroll their kids in COVID recovery interventions, and indeed we’re already seeing low uptake and interest in these programs. More broadly, parents need to support schools’ recovery efforts if the government is going to continue to fund them. In addition to helping kids catch up, these programs could be the nation’s best shot at narrowing the racial and economic achievement gaps that long predated COVID.

What to do? At minimum, parents need accurate, timely and accessible evidence about how their children are doing. And schools and districts need to engage with families, perhaps through new or regularly scheduled back-to-school or parent-teacher meetings. These efforts should include attempts to understand parents’ thinking about the impact of COVID and what children need now, as well as clear and honest appraisals of where children are relative to grade-level expectations and the options available to address any apparent deficiencies.

But we also think schools and districts should consider beefing up their optional COVID recovery programs and turning them into opt-out rather than opt-in. We are especially worried that the very students who need the support the most may be the least willing to voluntarily participate.

It is clear that COVID has affected kids’ learning, and that these effects for some children are quite large. But the messaging on those facts is clearly not reaching parents. If we can’t solve this disconnect, we won’t solve the underlying problem. And that would be the real educational disaster experts have been worried about.