PRESS RELEASE

Findings Incorporate Data on Weeks Remote and ESSER Dollars per District, Allowing Leaders to Re-calibrate Their Recovery Plans

Interactive Map Highlights Urgent Need to Add Instructional Time in Areas Hardest Hit

Today, The Education Recovery Scorecard, a collaboration with researchers at the Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University (CEPR) and Stanford University’s Educational Opportunity Project, released the first comparable view of district level learning loss during the pandemic utilizing the recently released 2022 NAEP data, and states who have publicly reported their district proficiency rates on their Spring 2022 assessments. These interactive district level maps include data from 29 states (plus DC) – where the necessary data was available.

CEPR Faculty Director Thomas J. Kane and Sean Reardon, Professor of Poverty and Inequality in Education at Stanford University and Director of the Educational Opportunity Project have used the 2022 NAEP scores to make state assessment results comparable. The new research, found on educationrecoveryscorecard.org, also incorporates data on weeks remote and the federal recovery dollars (ESSER) received per district, equipping state and local leaders with the information they need to re-calibrate their current recovery plans.

“The pandemic was like a band of tornadoes that swept across the country,” said CEPR Faculty Director Thomas J. Kane. “Some communities were left relatively untouched, while neighboring schools were devastated. The Education Recovery Scorecard is the first high-resolution map of the tornadoes’ path to help local leaders see the magnitude of the damage and guide local recovery efforts.”

“One of the things we found is that even within a district, there is variability. School districts are the first line of action to help children catch up. The better they know about the patterns of learning loss, the more they’re going to be able to target their resources effectively to reduce educational inequality of opportunity and help children and communities thrive.” Sean Reardon, Professor of Poverty and Inequality, Stanford Graduate School of Education.

- The average U.S. public school student in grades 3-8 lost the equivalent of a half year of learning in math and a quarter of a year in reading.

- Rather than rely on headlines about state achievement, parents and local officials need to understand how their local schools were affected. Six (6) percent of students were in districts that lost more than a year of learning in math, while 3 percent were in districts where math achievement actually rose.

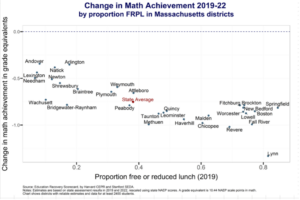

- The pandemic widened disparities in achievement between high and low poverty schools. The quarter of schools with highest shares of students receiving federal lunch subsides missed two-thirds of a year of math learning, while the quarter of schools with the fewest low-income students lost two-fifths of a year.

While many states and districts are using their portion of the $190B in federal aid to add tutoring and summer school and extended days, many of those efforts are not yet large enough to fully address the learning loss that has occurred. Using these estimates of achievement losses along with expected effect sizes for catch-up efforts and the share of students being served by each, districts now have an opportunity to make sure their plans are commensurate with their students’ losses.

Massachusetts

The project reports changes in test scores from 2019 to 2022 in grade equivalents. One grade equivalent represents approximately one school years’ worth of learning. Statewide, Massachusetts lost nearly seven months (-0.75 grade equivalents) of learning in math between 2019 and 2022, and lost nearly four months (-0.41) in reading. The data for individual districts varies widely, with some districts’ achievement losses amounting to almost a year. Below, we report estimates for a selection of the larger Massachusetts districts, which have the most precise estimates.

Examples of larger districts with losses in math:

- Lowell (-0.87) – equivalent to over seven and a half months in loss

- Worcester (-0.86) – equivalent to over seven and a half months in loss

- Boston (-0.85) – equivalent to about seven and a half months in loss

**1 grade equivalent is based on a 9-month school year. Divide the 2019-2022 change by 9 to get the number of months. For example, a .89-month loss would be an 8-month loss.

“We now see how much ground districts have to make up to get their students back on track. More than ever, we need district leaders to communicate with their communities on how they are using recovery funds to address those gaps,” said Marguerite Roza, Director of the Edunomics Lab.

Civil rights leaders see this new research as a call to action for state leaders to rise up a much bolder, aggressive response.

“Learning losses among minority students over the last two years have put the long-term vitality of the nation at risk. Latino and African American students make up nearly half of all students, making it a national imperative to invest in their academic recovery,” said Janet Murguia, the President and CEO of UnidosUS.

“If there is a sparkle of light during these dark times, it’s our nation’s historic infusion of funds through ARP and ESSER,” said John B. King, president of The Education Trust. “To address unfinished learning, we implore district leaders to invest in evidence-based strategies, including increased access to strong, diverse teachers, targeted intensive tutoring, expanded learning time, and strengthening socioemotional supports and relationships weakened during the pandemic.”

Kane said, “The whole village needs to hear the bell ringing, not just schools. Mayors should organize tutoring efforts at local libraries. Community organizations should plan school vacation academies and summer learning opportunities. Governors should be funding and evaluating innovative pilots to provide models that everyone could use. We cannot wait for the Spring 2023 state test results next fall to tell us that we underinvested in recovery efforts. Many are happy just to get back to normal, but normal won’t help kids catch up.”

About the Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University

The Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University, based at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, seeks to transform education through quality research and evidence. CEPR and its partners believe all students will learn and thrive when education leaders make decisions using facts and findings, rather than untested assumptions. Learn more at cepr.harvard.edu.

CONTACT: Lindsay Blauvelt at lindsay_blauvelt@gse.harvard.edu.