Harvard and Stanford Release Second Round of States for the Education Recovery Scorecard

Idaho Included in Total of 40 States That Have Comparable View of District Level Learning Loss

States Must Boost Summer Learning Opportunities, Add Instructional Time in Areas Hardest Hit

May 11, 2023 – Today, The Education Recovery Scorecard, a collaboration with researchers at the Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University (CEPR) and Stanford University’s Educational Opportunity Project, released a second round of research for twelve states that had not publicly reported their Spring 2022 assessment scores as of October last year. The research offers the first comparable view of district level learning loss that occurred as a result of the pandemic. The research findings utilized the 2022 NAEP data, and Idaho’s publicly reported district proficiency rates on their Spring 2022 assessments. With the second tranche of research, these interactive district level maps now include data from 40 states.

CEPR Faculty Director Thomas J. Kane and Sean Reardon, Professor of Poverty and Inequality in Education at Stanford University and Director of the Educational Opportunity Project have used the 2022 NAEP scores to make state assessment results comparable. The research, found on educationrecoveryscorecard.org, also incorporates data on weeks remote and the federal recovery dollars (ESSER) received per district, equipping state and local leaders with the information they need to reassess current recovery plans. In addition to the district level data for twelve new states, the researchers at Harvard and Stanford released a brief that offers insights into why students in some communities fared worse than others.

The Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University (CEPR) also created an interactive map on the press resource page that clearly shows the community-wide disparities between a handful of neighboring districts per state and underscores the need for a differentiated approach to recovery based on need.

“Children have resumed learning, but largely at the same pace as before the pandemic. There’s no hurrying up teaching fractions or the Pythagorean theorem,” said CEPR faculty director Thomas Kane. “The hardest hit communities—like Richmond, VA, St. Louis, MO, and New Haven, CT, where students fell behind by more than 1.5 years in math—would have to teach 150 percent of a typical year’s worth of material for three years in a row—just to catch up. It is magical thinking to expect that will happen without a major increase in instructional time. Any district that lost more than a year of learning should be required to revisit their recovery plans and add instructional time—summer school, extended school year, tutoring, etc.– so that students are made whole.”

“It’s not readily visible to parents when their children have fallen behind earlier cohorts, but the data from 7,500 school districts show clearly that this is the case. The educational impacts of the pandemic were not only historically large, but were disproportionately visited on communities with many low-income and minority students. Our research shows that schools were far from the only cause of decreased learning—the pandemic affected children through many ways – but they are the institution best suited to remedy the unequal impacts of the pandemic,” said Sean Reardon, Professor of Poverty and Inequality in Education at Stanford University and Director of the Educational Opportunity Project.

National Findings

- The median U.S. public school student in grades 3-8 lost the equivalent of a half year of learning in math and a quarter of a year in reading. This means that in spring 2022, students were half a year behind students in the same grade in spring 2019.

- Rather than rely on headlines about state achievement, parents and local officials need to understand how their local schools were affected. Eight (8) percent of students werein districts that lost more than a year of learning in math, while 3 percent were in districts where math achievement actually rose.

- The pandemic widened disparities in achievement between high and low poverty schools. The median student in the quarter of districts with the highest shares of students receiving federal lunch subsidies missed three-fifths of a year of math learning, while the media student in the quarter of districts with the fewest low-income students lost two-fifths of a year.

While many states and districts are using their portion of the $190B in federal aid to add tutoring and summer school and extended days, many of those efforts are not yet large enough to fully address the learning loss that has occurred. Using these estimates of achievement losses along with expected effect sizes for catch-up efforts and the share of students being served by each, districts now have an opportunity to make sure their plans are commensurate with their students’ losses.

“Schools were not the sole cause of achievement losses,” Kane said. “Nor will they be the sole solution. As enticing as it might be to get back to normal, doing so will just leave the devastating increase in inequality caused by the pandemic in place.”

Idaho Findings

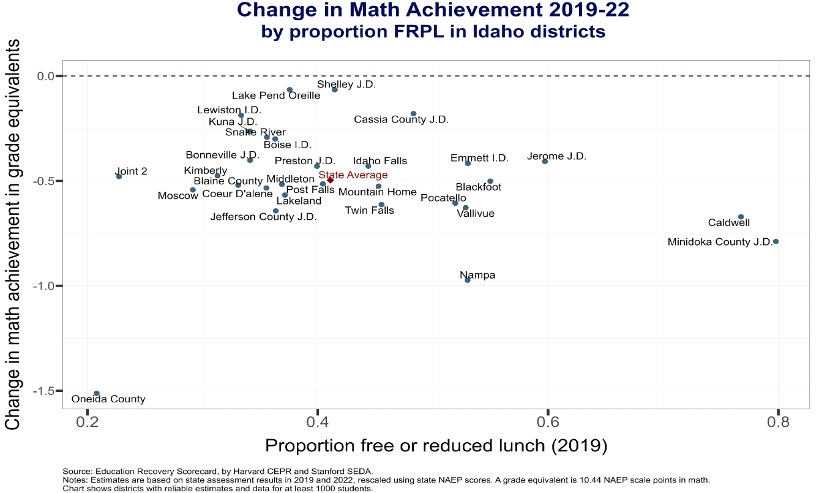

The project reports changes in test scores from 2019 to 2022 in grade equivalents. One grade equivalent represents approximately one school years’ worth of learning. Statewide, Idaho lost four and a half months (-.50 grade equivalents) of learning in math between 2019 and 2022 and nearly five months (-.54 grade equivalents) in reading, but the data for individual districts varies widely, with many districts’ achievement losses amounting to almost a year in losses in reading.

Below, we report estimates for a selection of Idaho districts, which — due to district size or proximity— may be of particular intrigue.

Significant district findings:

- Oneida County District had one of the largest learning losses in the country, where students experienced nearly fourteen months (-1.51 grade equivalents) in math and nearly twelve months (-1.31 grade equivalents) in reading.

- Shelley Joint School District 60 students experienced nearly a month (-0.07 grade equivalents) in math learning loss and nearly two months (-.19 grade equivalents) in reading learning loss. Nearby Gooding Joint School District students experienced positive changes of nearly a month and a half (.16 grade equivalents) in math and nearly a month (.11 grade equivalents) in reading.

- Nampa School District 131 students experienced nearly nine months (-0.97 grade equivalents) in math learning loss and nearly eleven months (-1.19 grade equivalents) in reading learning loss. Nearby Caldwell School District 132 students experienced six months (-0.67 grade equivalents) in both math learning loss and (-.68 grade equivalents) in reading learning loss.

- Boundary County School District 101 students experienced nearly five months (-0.54 grade equivalents) in math learning loss and over seven months (-.84 grade equivalents) in reading learning loss. Bordering Lake Pend Oreille School District 84 students experienced less than a month (-0.07 grade equivalents) in math learning loss and just over two months (-.29 grade equivalents) in reading learning loss.

**1 grade equivalent is based on a 9-month school year. Multiply the 2019-2022 change by 9 to

get the number of months. For example, a .89-grade equivalent would be an 8-month loss.

The Education Recovery Scorecard is supported by funds from Citadel founder and CEO Kenneth C. Griffin, the Carnegie Corporation of New York, and the Walton Family Foundation.

About the Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University

The Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University, based at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, seeks to transform education through quality research and evidence. CEPR and its partners believe all students will learn and thrive when education leaders make decisions using facts and findings, rather than untested assumptions. Learn more at cepr.harvard.edu.

CONTACT: Jeff Frantz | jeffrey_frantz@gse.harvard.edu | 614-204-7438